Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Ujjal al-Ghazwani was born in the city of al-Qasr al-Kabir (Ksar el-Kebir) in northern Morocco during the late Wattasid period. His father, Sidi Ujjal, was himself a righteous man known for his asceticism and spiritual wandering. According to Ibn Askar's Dawhat al-Nashir, Ujjal would travel through different lands with no fixed residence, entering markets and gatherings while calling out about his "lost camel," saying: "She is a camel with two sacks—she passed, she passed. Woe to one she deceived!" By this metaphor, he meant the worldly life (dunya).

A woman who knew Ujjal in her childhood reported: "Sidi Ujjal would come to my father's house when I was a young girl. When I would come to him, he would place his hand on my head and say, 'O Fa'ida (Benefit), you are a benefit!' He would say before the appearance of his son the Sheikh: 'I have a son whom I left studying knowledge. He will have great importance and will have as many followers as there are grains in a bunch of raisins—the large ones are sweet and the small ones are sweet.'"

Sidi Ujjal was greatly respected by the Emir of Chefchaouen, Moulay Ali ibn Rashid, who would pass his hands over the heads of his sons seeking blessings. Ujjal died in Qasr Kutama and was buried outside Bab al-Wadi, near the tomb of Sidi Abdullah al-Mazlum.

Abdullah received his initial education in religious sciences and literature in his hometown before traveling to Fez to pursue advanced studies.

While studying in Fez, young Abdullah heard about Sheikh Abu al-Hasan Ali Salih al-Andalusi, a renowned spiritual master. According to a famous story, Abdullah went to visit him at his zawiya with a group of students. The encounter profoundly moved him, stirring his inner being and awakening his aspiration for the spiritual path. When Abdullah asked Sheikh Ali Salih to guide him on the path of prophetic spiritual training, the Sheikh replied: "O my son, the master of this time is in Marrakesh. Go to him."

Sheikh Ali Salih directed him specifically to Sheikh Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz al-Tabba', known as al-Harrar (the silk worker). Some sources suggest that Abdullah may have first traveled to Granada in al-Andalus, where he studied under Sheikh Ali ibn Salih, and when the Sheikh left Granada, Abdullah followed him to Fez before being sent to Marrakesh.

Al-Ghazwani traveled to Marrakesh and attached himself to Sheikh al-Tabba', beginning what would become a transformative period of his life. Al-Nasiri records in al-Istiqsa: "In the beginning of his affair, he was studying in the Madrasa al-Wadi in the Andalusian quarter of Fez. Then spiritual aspiration (irada) occurred to him, so he traveled to Marrakesh and attached himself to Sheikh al-Tabba', graduating under his guidance."

Ibn Askar provides more detail: "The Sheikh commanded him to carry firewood to the zawiya and tend to the animals, and he remained in that state for a period. Then he employed him in guarding his garden and serving it."

This seemingly harsh treatment was actually a sophisticated spiritual pedagogy. Through years of menial labor—hauling wood, caring for livestock, maintaining orchards—al-Ghazwani learned humility, patience, perseverance, and the integration of physical work with spiritual practice. He was being trained not just in mystical states but in the practical skills of agriculture and water management that would later define his own approach to spiritual leadership.

After completing his training under Sheikh al-Tabba' and receiving authorization (ijaza) to guide disciples, al-Ghazwani traveled to the Hebt region, specifically to the Bani Fazkar tribe. There he established his first independent zawiya. His reputation spread rapidly, and people began flocking to him from every direction. The land buzzed with his fame.

However, this success brought unwanted attention from political authorities. Sultan Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn al-Sheikh al-Marini, the Wattasid ruler, became concerned about al-Ghazwani's growing influence. A jurist named Ibn Abd al-Karim al-Badisi al-Sufyani, who accompanied governors and accompanied their expeditions as judge, repeatedly slandered the Sheikh to the Sultan, warning that al-Ghazwani posed a threat to royal authority.

In 919 AH (1513 CE), the Sultan ordered al-Ghazwani's arrest. He was seized in a place called Tahnaout, placed in chains, and sent to Fez with instructions to the chief of police in Qasbat Fas al-Bali (Old Fez) to imprison him.

The timing of this persecution was significant. It occurred in the same year that Sheikh Muhammad ibn Ghazi, the leader of the scholarly community in Fez and imam of the Qarawiyyin Mosque, passed away. Ibn Ghazi had accompanied the Wattasid Sultan (known as "al-Burtuqali" - the Portuguese) on one of his military campaigns. During this expedition, Ibn Ghazi fell ill and asked to be carried back to Fez. As they approached the city, near the Aqaba al-Masajin (Prisoners' Hill) in the outskirts of Fez, his condition worsened and he ordered his companions to rest there.

At that very moment, al-Ghazwani passed by in chains, escorted by guards. When Ibn Ghazi saw him, he asked the guards to bring the prisoner to him so he could visit him in his illness. Ibn Ghazi supplicated for al-Ghazwani and then departed. This encounter between the dying scholar and the chained mystic became legendary.

Once imprisoned in Fez, al-Ghazwani demonstrated extraordinary spiritual powers. Ibn Askar relates that he informed the chief of police about astonishing matters, presumably predictions or knowledge of hidden things. The Sultan, hearing of these wonders, ordered his release, apologized to him, asked for his prayers, and requested that he reside in Fez.

Al-Ghazwani agreed to stay in Fez and built a zawiya just inside Bab al-Futuh (the Gate of Openings). This zawiya would later become the burial place of his distinguished student Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Ali ibn al-Talib. He remained there for a period, teaching and guiding disciples.

However, difficulties arose again. According to Hasan Jallab in Sab'at Rijal (Seven Men), al-Ghazwani's relationship with the Wattasids did not improve. He clashed with al-Nasir, the brother of the Wattasid Sultan, over a canal he dug from Wadi al-Laban (Milk River) to Fez to help people with irrigation during a year of drought. This public service project, intended to alleviate suffering during famine, was somehow perceived as problematic by the authorities.

Before leaving Fez, al-Ghazwani made a prophetic statement: "The matter has departed from the Bani Marin (Marinids/Wattasids) by my departure from them." This was a symbolic indication of the imminent Sa'di rise to power.

Al-Ghazwani returned to Marrakesh around 926 AH/1519 CE, where the Sa'di dynasty had consolidated its power. He established his final zawiya in the Qusur (Palaces) Quarter, an area that had historically been home to notables, scholars, and government officials. The neighborhood was close to the Almoravid nucleus of the city, founded near the present-day Koutoubia Mosque, where remnants of the Zuqaq al-Hajar (Stone Alley) still exist.

The Qusur Quarter became intimately associated with Sidi al-Ghazwani, and his zawiya became a center not just for spiritual instruction but for agricultural innovation and social welfare.

With his final settlement in Marrakesh and the establishment of his zawiya in the Qusur Quarter, al-Ghazwani embarked on what Muhammad Janbubi calls "a new journey in his life," one characterized by the practice he had perfected under his master al-Tabba': an integration of agriculture and spirituality.

Ibn Askar reports that "Sheikh Abu Abdullah al-Daqqaq, who was specially attached to him, told me: 'The Sheikh's habitual practice was movement in matters of plowing and extracting water.'" This wasn't merely a personal preference; it was a comprehensive vision for social and spiritual transformation.

Al-Ghazwani would tell his followers: "Whoever digs an irrigation canal makes food for people." This simple statement encapsulates a profound philosophy: that spiritual work and material development are inseparable, that serving God means serving His creation, and that feeding people's bodies is as important as nourishing their souls.

Historian Ibrahim Harakat notes in al-Maghrib 'Abr al-Tarikh: "Sheikh al-Ghazwani finally settled in Marrakesh, occupying himself with plowing and gardens, spending his income on those in need and contenting himself with the simplest food. He was devoted to digging irrigation canals and would task his companions with agriculture and extracting water. His method did not differ from his master's method."

Muhammad al-Mazuni, in "Zawiyat Tamṣluḥt During the Sixteenth Century," provides crucial context: "Al-Ghazwani's economic role in the Marrakesh region was the most important. He was a man who loved plowing and extracting water. His fame was confirmed in Fez, and his agricultural effort in the Haouz was viewed by many as more of a political act than a mere technical effort, because his insistence on plowing and irrigation was not explained by Sufi motivations as much as it was driven by the crisis of the Moroccan countryside and the negative results this crisis left on the human condition."

This analysis reveals the depth of al-Ghazwani's vision. Morocco in the early sixteenth century faced recurring droughts, famines, and economic instability. The Portuguese occupied coastal cities, disrupting trade. Political transitions from Wattasid to Sa'di rule created uncertainty. In this context, al-Ghazwani's agricultural projects were inherently political—they represented an alternative model of authority based on service rather than coercion, on development rather than extraction.

"He required his disciples to undertake these works as a fundamental condition in their Sufi training, and he would choose for them only damaged locations as sites for establishing their zawiyas," al-Mazuni continues. This was revolutionary: rather than building in fertile, prosperous areas, al-Ghazwani deliberately sent his students to barren, neglected lands with the mission of transforming them through irrigation, cultivation, and settlement.

Dr. Jamal Bami observes: "I see here—without exaggeration—a great sense of the necessity of providing food security, entertaining people, and relieving the distressed through land reclamation, digging canals, mastery of agricultural science, moving from 'words' to 'things' through field experiments, establishing gardens and nurseries, and integrating all of this within Sufi training and principled commitment."

He continues: "We are in dire need today of such a spirit as we raise the slogan of 'Green Morocco.' This noble goal requires knowledge and high determination like that which was available in al-Tabba', al-Ghazwani, and Ibn Husayn."

Dr. Bami identifies a profound understanding in these Sufi masters: "These imams internalized the danger of the Quranic verse 'and a well abandoned and a lofty palace' [Q. 22:45], and they rose to building and construction, fighting emptiness and bringing greenery, water, and prosperity. They realized that the existential necessities that connect humans to their cosmic earthly origin are the foundation of development and civilization—not the construction of palaces while wells dry up, nomadism spreads, and civilization contracts even if superficial appearances of urbanization proliferate."

This wasn't excessive interpretation, Dr. Bami insists, especially coming from a scholar of the role of plants, greenery, and spatial management in achieving prosperity.

Al-Ghazwani's students numbered in the thousands and established zawiyas throughout Morocco, creating a network of agricultural-spiritual centers. Among the most prominent:

Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Husayn al-Amghari (d. 976 AH/1568 CE), founder of the famous Zawiya of Tamṣluḥt in the Marrakesh region. A descendant of the Al-Amghar family from Ribat Tit and ancestor of the celebrated saint Moulay Ibrahim (known popularly as "Bird of the Mountains"), Ibn Husayn exemplified his master's teachings. He transformed barren lands through irrigation and agriculture as part of a comprehensive spatial development plan that al-Ghazwani had outlined. Paul Pascon's valuable study Le Haouz de Marrakech extensively discusses the role of Zawiyat Tamṣluḥt, which was a natural product of al-Ghazwani's school in fighting aridity and barrenness and bringing prosperity.

Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Sasi, founder of a famous zawiya on the banks of Wadi Tensift in the Haouz of Marrakesh, where he was buried in 961 AH/1553 CE.

Abu al-Nu'aym Radwan al-Janawi, who studied under al-Ghazwani in Marrakesh and remained there for about a year after the Sheikh's death before joining his master's zawiya in Fez, where he died in 991 AH/1583 CE.

Abu al-Hajjaj al-Talidi (d. 950 AH/1543 CE)

Abu al-Baqa Abd al-Warith ibn Abdullah

Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Uthman

Sheikh Abu Muhammad Abdullah al-Habti (d. 963 AH/1555 CE)

Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Isa al-Zamrani, known as "al-Talib" (d. 964 AH/1556 CE), whom al-Ghazwani appointed to head his zawiya in Fez.

Abu al-Hasan Ali al-Masmudi, who died in al-Qasr al-Kabir and whose grave is near the shrine of Sidi Ali Bu Ghalib.

Ibn Askar records that "Sheikh al-Habti informed me that the Pole Sheikh Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Jazuli used to train his companions with the poem of Sheikh Abu al-Hajjaj al-Darir on the principles of religion, and Sheikh Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz al-Tabba' used to train his companions with the fundamental investigations of the knowledgeable Sheikh Ibn al-Banna al-Saraqusṭi, and Sidi Abu Muhammad al-Ghazwani used to train his companions with the poem of Sheikh al-Sharishi."

This progression shows the evolution of Jazuli pedagogy: from al-Jazuli's emphasis on theological principles, to al-Tabba's focus on mystical philosophy, to al-Ghazwani's chosen text by al-Sharishi—each master adapting the curriculum to the needs of his time while maintaining the chain of transmission.

Al-Ghazwani's social roles manifested in feeding students, disciples, and common people, especially during famines and epidemics, in addition to digging canals and wells. His zawiya in the Qusur Quarter became a center for distributing food, providing shelter, and organizing relief during crises.

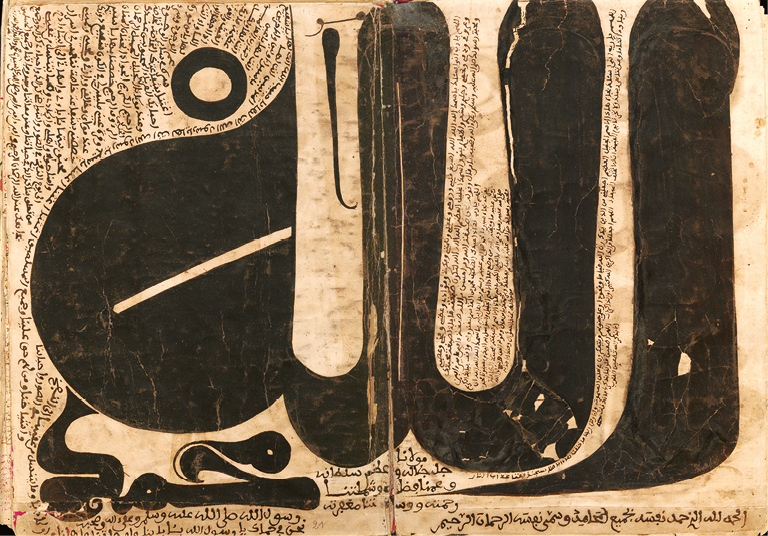

According to the Jesuit scholar Paul Nwyia in his book 'Abdullah al-Ghazwani (Moul Lqsur), the importance of al-Ghazwani lies in the fact that "he left us a collection of works, in both poetry and prose, through which we can discern the level of these Sufis' knowledge of unveiling sciences, the depth of their ideas, the solidity of their religious culture, and the strength of their spiritual personality—which justifies the accumulation of resounding descriptions with which they are characterized in biographical dictionaries."

Nwyia questions whether these elaborate titles were merely "artificial eloquence empty of any real meaning, or whether they had a basis in reality, bearing many true meanings." He cites the descriptions given by al-Kattani in Salwat al-Anfas: "The Sheikh, the Imam, the most knowledgeable scholar, the realizing Sufi, the perfect scrutinizer, the blessing of the age, the imam of the era, the sheikh of sheikhs, the knower of God's majesty and beauty, the caller to the divine presence through all his words and states, possessor of noble stations, pleasing states, lofty aspirations, subtle allusions, lordly gifts, gnostic secrets, the master of his time, the unique one of his age, the comprehensive Pole, the divine heir."

Nwyia notes: "We used to believe that high Sufi thought had emigrated from al-Andalus and the Maghrib with Ibn Arabi, Ibn Sab'in, al-Shushtari, al-Hurrali and others, and that the Maghrib after its return to the Maliki school during the Marinid era had returned to classical Sufism (as with al-Muhasibi) or to popular Sufism as with al-Jazuli in his Dala'il al-Khayrat. But al-Ghazwani speaks a different language—it is philosophical and esoteric on one hand, and deeply rooted in ancient Moroccan mentality on the other, to the point that he does not fear mixing in his correspondence between the riddles of eloquent Sufi terminology and Moroccan colloquial language. This gives his writing a special character and splendor—the splendor of things when we see them for the first time at dawn."

Al-Kattani noted in Salwat al-Anfas: "He has discourse on the Path in poetry and prose, but it is obscure—not understood except by one who has been opened to understanding."

In a manuscript Nwyia called "The Autobiography," part of a larger collection of poetry and prose titled Kitab al-Nuqta al-Azaliyya (The Book of the Eternal Point), al-Ghazwani writes:

"I listened to the ruling of their speech and the reality of their knowledge, and I looked into my reality: I found no answer within me, and I was unable to find the path of correctness. So I said to myself: I am among the veiled, among the idle, among the procrastinators, among the expelled, among the conceited, among the deniers, among the liars, among the deprived, among the counterfeit without reality, among those who speak without proof, among those who promise without success, among the sleepers without verification, among those who sit without realization...

"So I said: Far, far indeed! Bring near the distance, O You who say to a thing 'Be!' and it is. I scrutinized them carefully and saw that their appearance was not like the appearance of those standing on ruined pulpits, not like the gathering of those sitting on cracked chairs, not like the gathering of the haters and deniers, not like the gathering of those who deny and turn away, not like those who face the qibla without certainty, not like those who practice the Sunnah of our Prophet Muhammad without reality, not like the gathering of those who speak without insight or true clear explanation, not like the gathering of those who speak with words but do not know the reality of states...

"When I awoke, was certain, and realized, I saw in them the mark of prophetic influence, and they established themselves through realizing the reality of the Sunnah, gathering for the finest goal of the religion. God inspired me to a verse from His Book, which is His saying: 'Soon God will bring forth a people whom He loves and who love Him' [Q. 5:54]. So I became annihilated in their love...

"Then the knowledgeable master said to me: 'Cast aside your weapons and take a name from my name so that you may attain comfort.' He gave me the name 'May God be pleased with him—he does not become poor,' and 'Strong—he does not tear apart,' and 'Mighty—he does not cease,' and 'Described with majesty,' and 'Described with honor,' and 'Glorified and eternal.'"

This mystical prose reveals al-Ghazwani's sophisticated understanding of the spiritual path, combining philosophical depth with personal authenticity.

Nwyia notes: "If al-Ghazwani returned to Marrakesh in 926 AH/1519 CE, his residence and work there lasted nine years, because he died in 935 AH/1528-1529. The apparent cause of his death was a heart attack, according to what historians mentioned."

Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Fasi, in Tuhfat Ahl al-Siddiqiyya, describes his death: "One day he went out, as was his custom, to the countryside for reconciliation, and his companions went out with him. They were away for a while, then they returned. When they were near the city and he was riding his horse, traveling on the road, they saw him lean from his horse. They rushed to him and found that he had died. They carried him to the city and buried him in his zawiya in the Qusur Quarter inside Marrakesh. They built over him a magnificent dome, and it is a great, famous pilgrimage site."

His tomb became one of the most visited shrines in Marrakesh, and he is counted among the city's Seven Saints. The zawiya in the Qusur Quarter remains an active site of visitation and spiritual gathering to this day.

Find all our meditations on the Nur App!

Experience tranquillity through Qur'anic recitations and meditations on our Nur App and develop healthy spiritual routines to maintain your God-given Nur (light).