In the chronicles of Marrakesh's spiritual heritage, few figures embody the virtue of patience and submission to divine will as profoundly as Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji. Known by multiple titles—"al-Mubtala" (the Afflicted), "Abu Ya'qub," and most famously "Mul al-Ghar" (Man of the Cave)—this sixth-century Hijri saint transformed personal suffering into spiritual elevation, becoming a living example of unwavering faith and contentment with God's decree. His story, though marked by physical hardship, shines as a beacon of hope and resilience for all who face adversity.

Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji was born in Marrakesh to a family of Yemeni Arab origin. Unlike many of the other saints whose biographies are rich with details about their education and travels, the historical sources remain largely silent about his birth date, childhood, and early years. According to the historian al-Ifrani in "Durar al-Hijal," some accounts suggest he may have been related to the great Sufi Abu Madyan Shu'ayb ibn al-Husayn al-Ansari, who is buried in al-'Ubbad near Tlemcen and died in 594 AH/1197 CE, though this relationship is mentioned only by al-Ifrani without citation of sources, and other historians do not confirm this connection.

What we do know is that Yusuf ibn Ali studied under Sheikh Abu 'Usfur (Ya'la ibn Wayn Yufan al-Jadham), one of Marrakesh's most distinguished spiritual masters of his time, who passed away in 583 AH/1187 CE. Abu 'Usfur himself was a disciple of the legendary Abu Ya'zza Yalnur ibn Maymun (d. 572 AH/1176 CE), who was also the teacher of the great Abu Madyan al-Ghawth. This illustrious spiritual lineage placed Sidi Yusuf within a blessed chain of some of the most prominent saints and spiritual guides of Morocco, connecting him to the very heart of Maghribi Sufism.

Ibn al-Zayat al-Tadili, in his seminal work "al-Tashawwuf," described him as "a student of Sheikh Abu 'Usfur. He lived in the lepers' quarter, south of the city of Marrakesh, and there he died in the month of Rajab in the year 593 AH, and was buried outside Bab Aghmat at Ribat al-Ghar."

In the prime of his youth, Yusuf ibn Ali was afflicted with leprosy (judhham), a disease that was both physically devastating and socially isolating in medieval times. According to some accounts, this illness led to his banishment from his family and from living within the city walls—a common practice for those suffering from contagious diseases. However, it is crucial to understand this "banishment" within its proper historical and social context.

During the Almohad period, the establishment of lepers' quarters was not an act of cruelty or abandonment, but rather part of an organized healthcare and social welfare system. The Almohad state, particularly under Sultan Ya'qub al-Mansur, showed remarkable concern for public health, building hospitals (bimaristans), establishing separate quarters for those with infectious diseases, and providing for their needs through endowments and charitable donations.

The historian al-Hasan al-Wazzan (Leo Africanus), describing such a quarter during the Sa'di period in his "Description of Africa," noted: "It contained approximately two hundred houses, and they had their leader who collected the income from numerous properties endowed for their benefit for the sake of God by notables and other benefactors, and he provided these patients with everything necessary so that they lacked nothing."

Similarly, the geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi mentioned the lepers' quarter in Fez (Rabat al-Kiyyan), and Ibn Abi Zar' and al-Jaznai explained that such quarters were deliberately placed outside city gates—in Fez outside Bab al-Khukha, in Marrakesh outside Bab Aghmat—to be "under the flow of western winds, so that the winds would carry their vapors and nothing would reach the city's inhabitants, and so that their use of water and washing would be after they left the city." This was not neglect but rather an application of medical understanding about disease transmission and environmental health.

The scholar al-Husayn Boulaqtib, in his book "Epidemics and Plagues in Morocco During the Almohad Era," notes that Sultan Ya'qub al-Mansur built a magnificent hospital in Marrakesh that was unparalleled in the world at that time. The contemporary historian Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi provided a detailed description, noting that the Sultan allocated thirty dinars daily for food alone, established pharmacies within it for preparing medicines, provided clothing for patients, and even gave departing poor patients money to live on until they recovered fully. The French historian René Millet compared this hospital favorably to European medieval hospitals, declaring that it even surpassed Parisian hospitals of the early twentieth century.

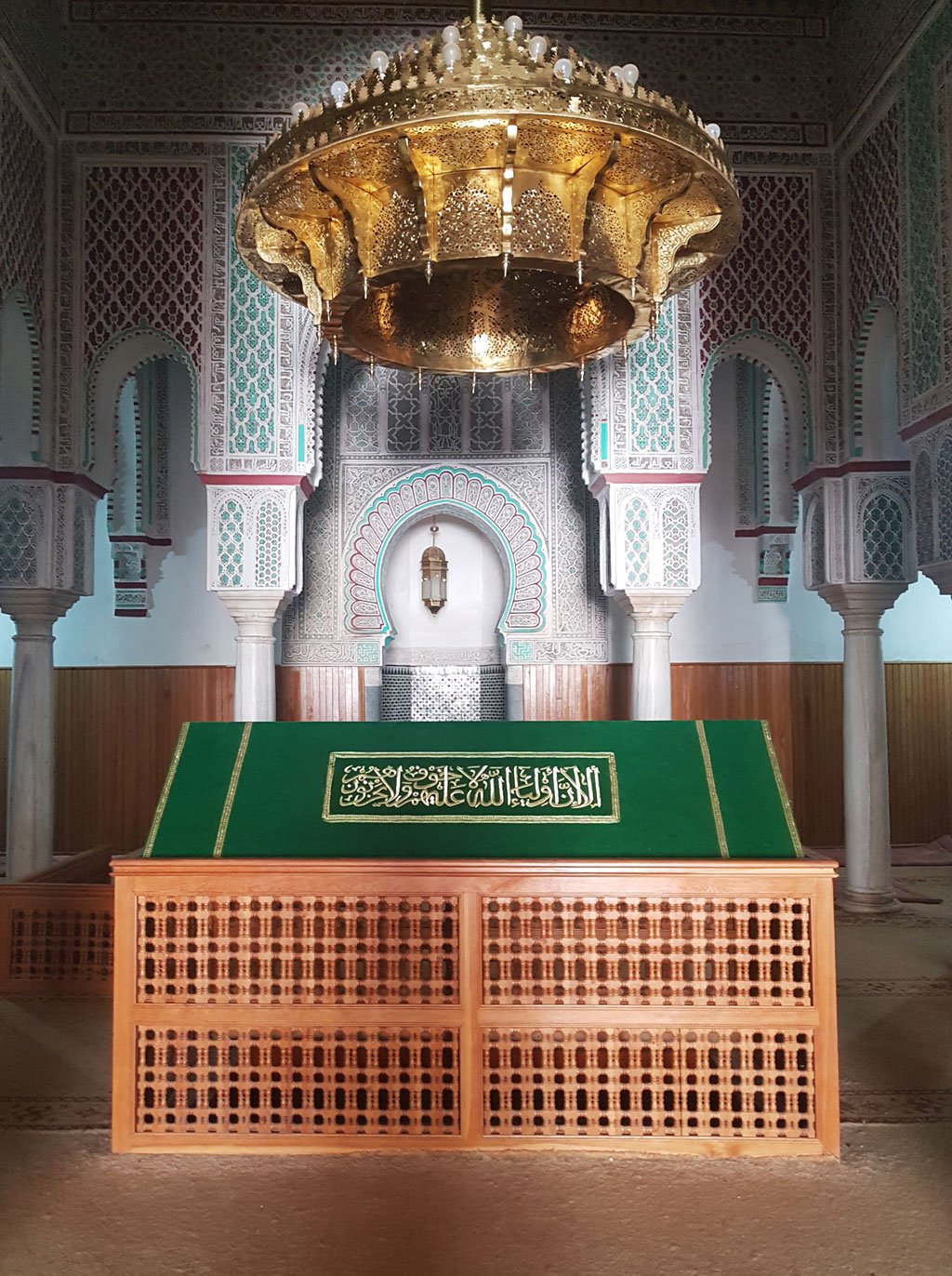

Unable to remain in the city proper, Yusuf ibn Ali took up residence in a cave he either found or dug himself in the lepers' quarter outside the southern gate of Bab Aghmat. This cave would become so identified with him that he earned the sobriquet "Mul al-Ghar" (Man of the Cave). The location was also known as "Ribat al-Ghar" (the Hermitage of the Cave), indicating it had become a recognized place of spiritual retreat and devotion.

The cave that still exists today within the shrine of Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali can be accessed via a small staircase. The coffin visible in the center of the shrine is a symbolic extension of the actual grave located inside the cave—a testament to the historical authenticity of this site.

In this humble cave, far from the comforts of city life, Yusuf ibn Ali transformed his affliction into a spiritual gift. Rather than succumbing to despair or bitterness, he devoted himself entirely to worship, contemplation, and submission to God's will. His patience in the face of his illness became legendary, and he came to be compared to the Prophet Job (Ayyub), known in Islamic tradition as the epitome of patience during trials.

Ibn al-Zayat al-Tadili, who visited Yusuf ibn Ali several times, recorded: "He was a man of great importance, virtuous, patient, and content. When parts of his body fell away at times, he would prepare abundant food for the poor in gratitude to God Almighty for that." This remarkable response—thanking God even as his body deteriorated—exemplifies the highest levels of spiritual realization.

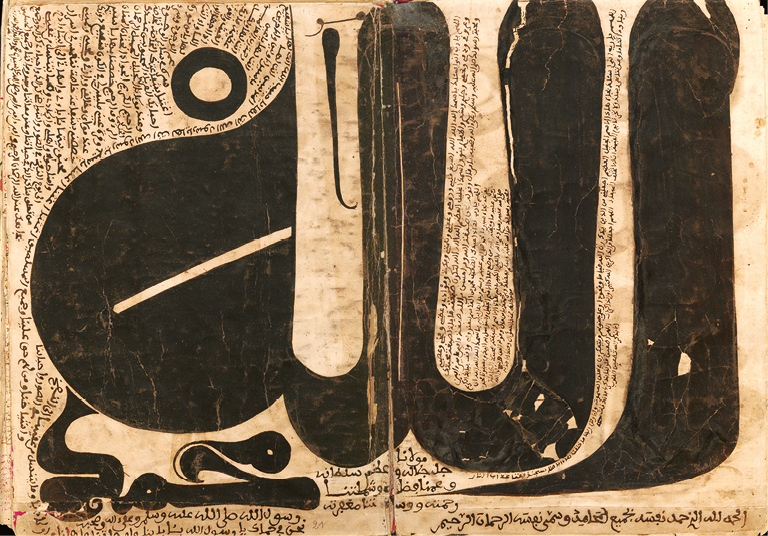

The saint himself composed poetry expressing his philosophy:

"I became accustomed to the touch of harm until I grew familiar with it,

And the length of affliction delivered me to patience."

Despite knowing almost nothing about Yusuf ibn Ali's scholarly activities, his teaching methods, or the nature of his instruction, the historical sources focus intensely on his exemplary patience (sabr) and contentment (rida) with divine decree. He was given the title "al-Mubtala" (the Afflicted One), and became proverbial for his forbearance, earning comparison to the Prophet Job.

Al-Ifrani wrote in "Durar al-Hijal": "The Sheikh who manifested the water of secrets after it had disappeared, and displayed from the station of contentment what made every knower feel ashamed and protective... Abu Ya'qub Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali, the Man of the Cave..." He added: "He displayed from the station of contentment what made every knower feel ashamed, and this is the highest of all stations, for he is at the supreme end of spiritual knowledge."

Yusuf ibn Ali achieved multiple spiritual stations simultaneously. Beyond patience, he embodied gratitude (shukr), praise (hamd), generosity (jud), and nobility (karam). Despite his poverty and difficult circumstances, he was known for his generosity to the poor and his constant state of thankfulness. Ibn al-Zayat noted that he was visited by people who received from him "love and affection," and that crowds would gather for his funeral, demonstrating his status and the people's recognition of his spiritual rank.

One of the most fascinating stories preserved by al-Ifrani in "Durar al-Hijal" demonstrates that despite his seclusion, Yusuf ibn Ali possessed keen insight into worldly affairs, particularly politics. During his time, there was an Almohad governor in Marrakesh known for his harsh rule and difficult temperament. The people complained about his poor governance, and the city's notables decided to seek his removal and replacement. They were advised to consult Abu Ya'qub (Yusuf ibn Ali) for counsel.

They found him sitting outside his cave in the sunshine, as was his custom, with his legs extended and covered with many flies. As the notables of Marrakesh approached, he called out to them: "Stop there and do not come near me, lest these flies that have already fed on me fly away and hungry flies come to me."

The delegation immediately understood his metaphorical message: "Leave this governor you have, for he has already fed himself. If you depose him and bring another, he will come to you hungry and will not be satisfied until he has harmed you even more."

Al-Ifrani commented on this incident, revealing his own political philosophy: "It is clear that in Abu Ya'qub's indication there are subtleties, as if he was saying to them: You are people of evil, and your deeds are ugly. No one will come to you except one who will govern you as this governor does, for he only oppressed you after you yourselves deviated from the straight path."

Whether this story is historically accurate or apocryphal, it transmits important political discourse and reveals aspects of political thought during the Almohad period and afterward. It demonstrates that the saint's reputation extended beyond mere piety to encompass wisdom applicable to practical affairs of governance.

The poet and scholar Abu al-Hasan al-Yusi, in his famous 'Ayniyya poem about the Seven Saints of Marrakesh, gave Yusuf ibn Ali a prominent place, testifying to his enduring fame:

"In Marrakesh appeared stars rising,

Mountains firmly rooted, nay, cutting swords.

Among them is Abu Ya'qub, the man of the cave, Yusuf,

To whom fingers point in reverence."

The poem continues by naming the other six saints: Qadi 'Iyad, Abu al-Abbas al-Sabti, al-Jazuli, al-Taba', al-Ghazwani, and al-Suhayli, placing Yusuf ibn Ali in illustrious company among the spiritual luminaries of the city.

Yusuf ibn Ali passed away in the month of Rajab, 593 AH (1196 CE), and was buried outside Bab Aghmat at Ribat al-Ghar, beside his teacher Sheikh Abu 'Usfur Ya'la ibn Wayn Yufan (d. 583 AH/1187 CE) and Sheikh Abu 'Imran al-Haskuri al-Aswad (d. 590 AH/1193 CE). Despite his illness and the physical limitations it imposed, he lived longer than anyone expected, which many interpreted as evidence of his spiritual powers and divine favor.

During the Sa'di period, this lepers' quarter was relocated from Bab Aghmat to outside Bab Doukkala, in the area now known as al-Hara. Al-Ifrani explains in "Durar al-Hijal": "They remained there until the state of the Sharifian Sa'dis, who moved them to the west of Marrakesh outside Bab Doukkala, shifting them from the eastern side to the western side for reasons that necessitated that."

In the sixteenth century, specifically in 934 AH/1527-28 CE, the Sa'di Sultan Moulay Abdallah al-Ghalib built a magnificent mausoleum and zawiya over the cave where Yusuf ibn Ali was buried. The sultan's motivations for this construction are not entirely clear, but scholars suggest it may have been a conciliatory gesture related to his displacement of the leprous population from Bab Aghmat to Bab Doukkala, or perhaps recognition of the saint's importance to the city's spiritual identity.

Al-Ifrani, who was personally present during later renovations, provides detailed architectural information about the shrine. He records that in the year 1134 AH (1721-22 CE), a devastating flood entered the cave and mosque, destroying houses in the village built around the cave and causing great material damage. The city's governor at that time undertook major reconstruction, building the dome that exists today.

Al-Ifrani explains: "They excavated the entire cave until the shrine of Abu Ya'qub became exposed to the sun, and he wanted to leave it that way, but it was said to him: 'It would be better if you concealed his shrine as it was before.' So he roofed over the shrine above pillars, then built the dome above that, so the shrine remained in a basement. Whoever wishes to descend to it may descend by stairs, and whoever wishes may visit the upper shrine, for it is aligned with the shrine that is below in the basement."

Al-Ifrani adds a personal note: "I was present for all of that, and I am one of those who advised the aforementioned governor about what was suggested to him."

Yusuf ibn Ali's reputation grew over time until he became one of the most celebrated saints of Marrakesh. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Isma'il instituted an annual pilgrimage (ziyara) to the Seven Saints of Marrakesh, establishing an order for visiting their tombs. Significantly, the shrine of Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali became the first stop on this pilgrimage route, a position of honor that reflects his importance in the city's spiritual hierarchy.

The neighborhood and suburb surrounding his mausoleum are today part of the local prefecture of Sidi Youssef Ben Ali, named after the saint. This administrative designation ensures that his name and memory remain part of the daily life of Marrakesh residents, connecting past and present in a living tradition.

Modern scholars have reflected deeply on the significance of commemorating Yusuf ibn Ali and emphasizing his school of patience. Dr. Jamal Bami suggests that this emphasis represents both an acknowledgment and a corrective to any negative perceptions of lepers and those afflicted with infectious diseases that may have existed in collective memory. He writes: "We are witnessing an 'announcement of consciousness' about the value of the theme of patience, embodied here in its most beautiful form in the personality of this righteous man whom the hagiographies compare to the Prophet Job."

The transformation of Yusuf ibn Ali from one afflicted by disease to one of the Seven Saints of Marrakesh demonstrates a profound Islamic principle: that true nobility lies not in physical health, social status, or material circumstances, but in one's relationship with God and response to His decrees. His elevation to sainthood while living with leprosy in a cave challenged social prejudices and reminded the community that divine favor and spiritual rank are not determined by worldly conditions.

Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji lived a life that most would consider unbearably difficult. Afflicted with a disfiguring, painful, and socially isolating disease, dwelling in a cave outside the city walls, watching his body deteriorate piece by piece—these circumstances would break most people's spirit. Yet Yusuf ibn Ali transformed these trials into spiritual triumph.

His secret lay in his understanding that patience (sabr) is not passive resignation but active acceptance of divine wisdom. Each loss of flesh became an occasion for preparing food for the poor in gratitude. Each day of suffering deepened his intimacy with God. The cave that society saw as a place of exile became for him a sanctuary of divine encounter.

His poetry captures this transformation:"I became accustomed to the touch of harm until I grew familiar with it,

And the length of affliction delivered me to patience."

What begins as suffering becomes familiar, and familiarity leads to patience, and patience opens the door to contentment and spiritual realization. This is the "school of patience" that made even the greatest spiritual masters feel ashamed before his example, as al-Ifrani noted.

More than eight centuries after his death, the shrine of Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali continues to draw visitors seeking blessings, guidance, and inspiration. The great scholar Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti mentioned visiting the shrine more than five hundred times, demonstrating the site's importance to scholars and common people alike.

In an age when people are quick to complain about minor inconveniences, when suffering often leads to despair or bitterness, the example of Sidi Yusuf ibn Ali offers an alternative paradigm. He shows us that affliction can be a path to elevation, that loss can lead to gain, that what appears as curse can reveal itself as blessing—if we meet our trials with patience, gratitude, and trust in divine wisdom.

His life reminds us that God does not measure us by our health, wealth, or comfort, but by the state of our hearts. A man living in a cave with leprosy proved to have a more beautiful soul and higher spiritual rank than many who enjoyed every worldly advantage. This is the essence of Islamic spirituality: true nobility is nobility of character and closeness to God, which are available to anyone regardless of their external circumstances.

The cave that once isolated him now unites people in remembrance and aspiration. The disease that once marked him as afflicted now marks him as blessed. The patience that once sustained him through personal trial now sustains countless others who visit his shrine and are reminded that no hardship is too great when met with faith, no suffering is wasted when offered to God, and no trial is permanent except in the lessons it teaches and the character it builds.

May God sanctify his secret, grant us his patience in our trials, and allow us to transform our afflictions into opportunities for drawing closer to the Divine. May his example continue to inspire those who suffer, comfort those who grieve, and remind all of us that the path to God's pleasure sometimes leads through the cave of hardship to the palace of proximity.

Fatiha.

Find all our meditations on the Nur App!

Experience tranquillity through Qur'anic recitations and meditations on our Nur App and develop healthy spiritual routines to maintain your God-given Nur (light).